‘But when Herod’s birthday was kept, the daughter of Herodias danced before them, and pleased Herod. Whereupon he promised with an oath to give her whatsoever she would ask. And she, being before instructed of her mother, said, Give me here John Baptist’s head in a charger.’ The event that leads to the beheading of John the Baptist is related in a few brief sentences in the gospels of Matthew and Mark. The step-daughter of Herod, tetrarch of Galilee, is as yet nameless here, and her egregious demand does not arise from her own will but that of her mother Herodias, who hates the troublesome prophet. What will make Salome (her name is recorded for the first time in the fifth century) into a myth is, however, clearly addressed: the act of displaying herself in the dance to the eyes of others, and with this the fascination of the onlooker and the power that the object of his gaze exercizes over him. It seems as if centuries of artists, in particular painters, have felt the sober account of the biblical narrative as a never-failing source of inspiration to give the story sensory concreteness and enrich it in the most diverse detail.

In late 19th-century French literature the figure of Salome became a popular subject as a femme fatale and the epitome of perverted lust. The climax was reached with Oscar Wilde’s tragedy Salomé, written in French and breathing the spirit of the fin de siècle. Expanding the original constellation of gazes, Wilde weaves a whole web of obsessive and unreturned gazes between the figures, as the expression or origin of desire. Can one evade the gaze, as Jochanaan believes when he attempts to forbid Salome to look at him ‘with her golden eyes, under her gilded eyelids’? Can the gaze be denied and the word alone be trusted? Wilde’s tragedy unfolds between the oppositions of eye and ear, physicality and spirituality, sound and word, looking and insight.

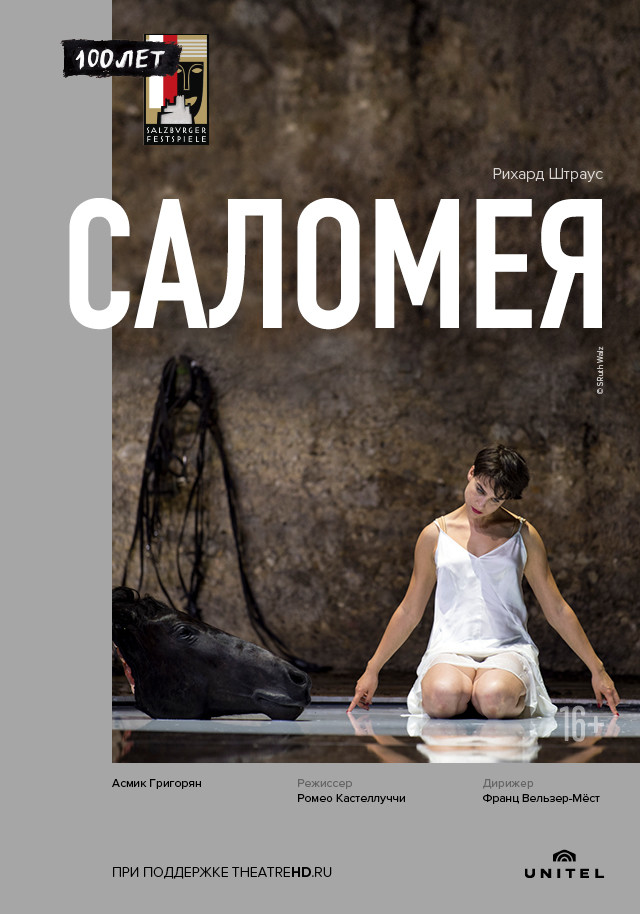

When Richard Strauss began to set an abridged German translation of this scandal-ridden play to music in 1903 he faced the challenge of conveying these antitheses in the medium of music – or indeed of relativizing them. As a composer, with Salome Strauss now found a language of his own in the sphere of opera as he had previously done in his symphonic poems, the hitherto unsuspected wealth of orchestral colours being just one of its unmistakable characteristics.

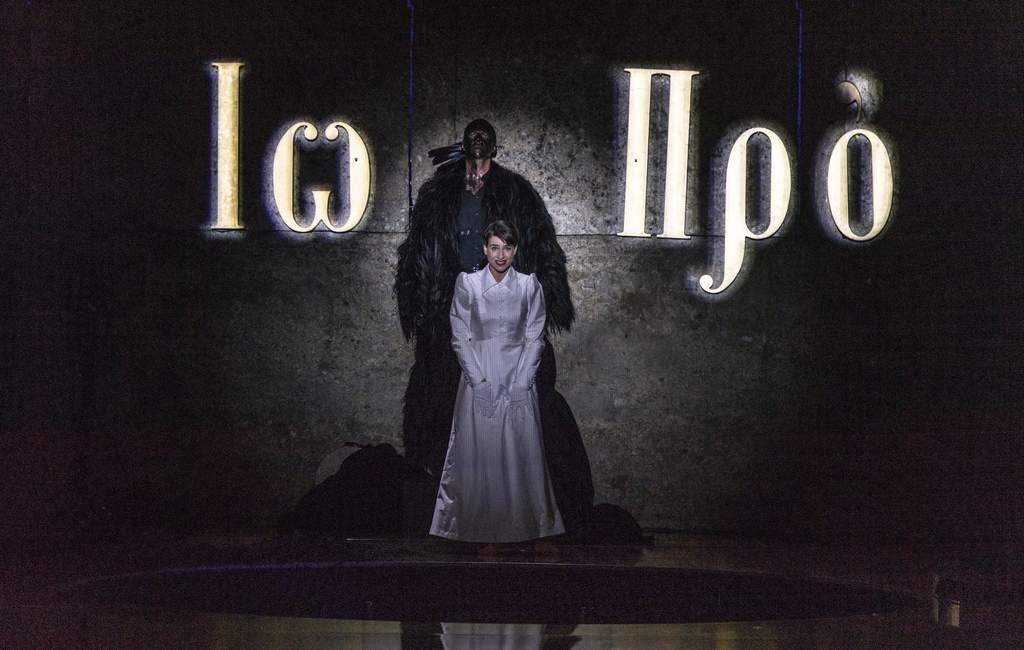

The Italian director Romeo Castellucci, a profound investigator of the power of seeing, also in the sense of that by which we are seen, will explore the darknesses of this ‘tragedy of the gaze’. An artist with an exceptional ability to create images that pulsate with knowledge of the unconscious, he approaches Salome by assuming the place hosting the theatrical action as his point of departure. By means of an intervention in the classic appearance of the Felsenreitschule with its arcades hewn from the rock of the Mönchsberg the impression of suffocation is suggested. It could be perceived as the objective correlative to the feeling of oppression that surrounds the protagonist on all sides and which pervades the music and the game of catch played out by the repetition of words throughout the libretto.

The staging conceived for Salzburg makes the figure of Salome the true pivot, transforming her into the fire that animates all that is present, and which in the dance of the seven veils blazes up and is consumed. The dance forms a climax, a manifestation of intensity and a final flaring up that touches the spectator.

In a scenic image in which sublime elements exist alongside the mundane, Romeo Castellucci’s staging foregrounds less the yearning for the trophy of Jochanaan’s head than the act of cutting, cutting away; not the object of desire, which is lost forever, but the touching loneliness of a female figure for which we feel sympathy. And it is here that the act of looking, by virtue of its ultimate interdiction, plunges into the abyss of desire.